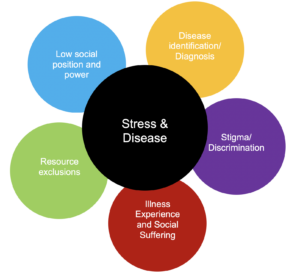

I deploy an array of theories and methods from social science to unravel the complex and fundamental intersections between culture, health, environment, and well-being. Specifically, I (mostly) study how disempowered or marginalized social positions and resource insecurity interact with meanings, daily experiences, and felt emotions to shape psychosocial stress (or lack of it) and physical and mental health.

Basically, my goal is to unravel the mechanisms that connect low power to worse health, to reduce human suffering and create health and wellbeing. As part of this, I work in large, diverse, collaborative teams. I also work with groups outside of academia before, during, and after projects – local communities, international development agencies, other state and private institutions like hospitals or NGOs, and/or elected leaders – to identify the very best ways to translate anthropological research into sustainable, meaningful solutions.

I also have research interests in how to teach anthropology better, and how to get anthropological tools deployed in medical and international development interventions. At any time, we have varied projects at different stages. What follows is a sample.

How Can We Improve Household Water Insecurity?

For some years, I have been innovating biocultural approaches to understand the mechanisms connecting water insecurity, culture/social dynamics, and stress. This research is connected to the HWISE research collaborative network, initially funded by the National Science Foundation. The effort brings together scholars and practitioners from all around the world to better document the lived experience of water insecurity.

A main focus in my research on water insecurity has been in understanding the biocultural mechanisms that link water insecurity to worse health and mental health outcomes, and so determine the best points for effective intervention. For example, many households globally struggle daily with water insecurity, food insecurity, and common mental illnesses like depression. But how do we unravel these? For example, if we can produce consistent evidence that water insecurity drives household food insecurity, this then suggests food insecurity interventions must begin by securing household water access. If water insecurity explains the effects of food insecurity of depression and anxiety, then mental health interventions have new clues about what will be most effective.

Analysis and write-up of data collected in Haiti in 2018 and Ethiopia 2019 is now completed. Ethiopia research is in collaboration with Haramaya University (HU), Ethiopia. Here’s some more about the work and our key HU collaborator Dr Kedir. Community-based data collection is ongoing in Mexico-US border colonias, peri-urban Apache Junction, and elsewhere in Arizona, as part of a broader HWISE effort to develop new water insecurity tools for understanding and fixing water insecurity in higher income countries (including the US) and in support of the goals of the Arizona Water Innovation Initiative.

How Can Increase Community Input in Intervention Design? The Global Impact Collaboratory [GIC]

How do we know that our projects will or do have a meaningful, sustainable impact? Launched in 2015, the Global Impact Collaboratory (GIC) tests the best ways to bring innovative ethnographic methods into development program design, monitoring, and evaluation. We are always happy to talk to people about how anthropology can improve development, and manage contracts to help programs improve the monitoring, evolution, and learning. Recent USAID-supporting projects have been located in Mozambique (coastal climate adaptation), Haiti (rule of law), and Zambia (community conservation). You can read about the Mozambique work here.

How Does Disease Diagnosis Damage our Social Identities?

When a disease is diagnosed it often changes who you are as a person — how you see yourself and how others relate to you. Often the act of receiving a diagnostic label disconnects you from others, such as through stigma. But other times it can be a social connector, bringing you back into society instead. This is often the case for conditions where there is no biomarker or test that can demonstrate that illness and debilitation “exist” other than in the person’s own telling. In such cases, the diagnostic label in itself returns social legitimacy and can bring more social support to the person who is suffering. This is a book project in progress.

The Global Ethnohydrology Study [GES]

Running strong since 2006, the Global Ethnohydrology Study (GES) studies local cultural knowledge and coping with water insecurity and other challenges of living with climate change. To date, we have collected data in 20+ different countries, and at multiple sites within the US. The GES is a signature project that not only collects important research data, but also is committed to training cohorts of students in field collection and lab analysis of cultural data; to date, thousands of students and dozens of experts from an array of fields have participated. Some information about and publications from this study can be found here. In 2021-22, we collected extended interview data in three South Asian countries to understand how women use language to reclaim their dignity around a humiliating, deeply-distressing phenomena called “period poverty.” In 2022-23, we are examining the idea of “moral economies” of water. In 2024-25, we are testing how the entwined physical and emotional experiences of thirst are similarly/differently recognized and interpreted across diverse sites where thirst and water insecurity are more common.

Introducing: ANTHROPOLOGY!

I was an early adopter of asynchronous online instruction, and have taught 1000s of online students in lower division anthropology every year for well over a decade. I have taught students in all parts of the globe, including those variously institutionalized and even stationed on a submarine. I continue to be energized by the possibilities: It can reach so many non-traditional, diverse students, and — if done right — is the means to communicate to (an often skeptical) wider public audience the value and relevance of anthropology. But this level of scaling is something rather new to anthropologists. Introducing: Anthropology! is a collaborative effort to find easy, scalable strategies that can instill a deep and enduring appreciation of our dynamic and complex field for undergraduate non-majors. We are proposing some best practices through a careful review of what is happening in classrooms (virtual and otherwise) and then testing which strategies yield the highest impact. For example: When does a generalized introductory course feed student excitement and imagination compared to those focused on a sub-field, or experientially-focused courses? What are the most effective ways to build the benefits of experiential learning into very large online introductory courses? What do diverse students recall as the important points and insight well after courses have finished, and why? What approaches to teaching online versions of introductory anthropology prove most satisfying and meaningful to anthropologist-instructors, and why?

What Does it Mean to Have a Big Body? The Small World/Big Bodies Project

Bodies almost everywhere are getting larger, in what is termed an “obesity epidemic.” For the last 3 decades, I have been working across the globe to understand changing stigma toward “fat.” You can read the NYTimes coverage of our seminal 2011 findings. In 2021 we published a book — “Fat in Four Cultures” –based on ethnographic fieldwork in Japan, Paraguay, Samoa, and the US, a comparative study of what it is means to live with weight worries. Another aspect of the project is investigating how “fat talk” works in different cultural settings.

Citizen Social Science in Global Health (C-SIGH)

Citizen science (CS) is a potentially fun means to scale our research, encouraging wider public participation in research adventures. CS has been widely applied in the natural sciences. But very little CS has been done in social science, in part because you need good observers of social phenomena. Using Phoenix as our test-bed we are investigating a fundamental question: what makes a good citizen social scientist? And how does this connect to our efforts to advance a global health that is better connected to community needs and concerns? : Cindi SturtzSreetharan is leading this effort.

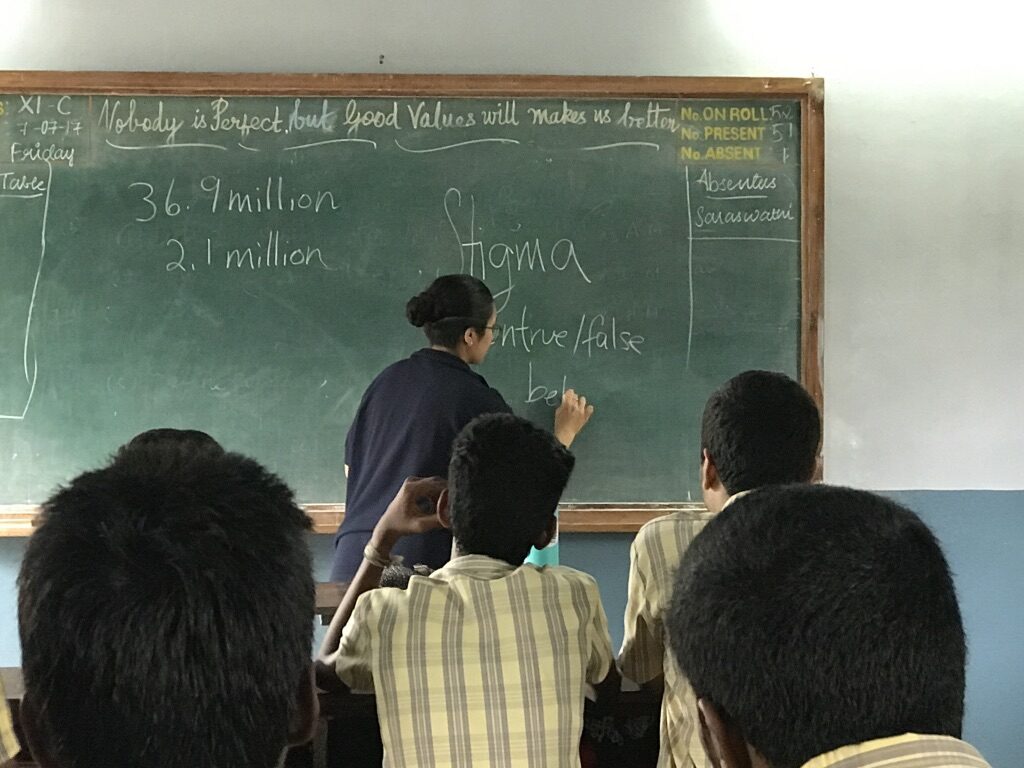

Reducing Stigma in Global Health Practices

Pulling from our decades of work in low-resource communities across the globe, we are synthesizing understandings of the ways that global health efforts can inadvertently damage those is means it serve by creating or reinforcing social stigma. It’s a project to directly challenge conventional thinking in public health. We have a book out with Johns Hopkins University Press that introduces our concerns, ethnographic insights, and suggests some solutions.

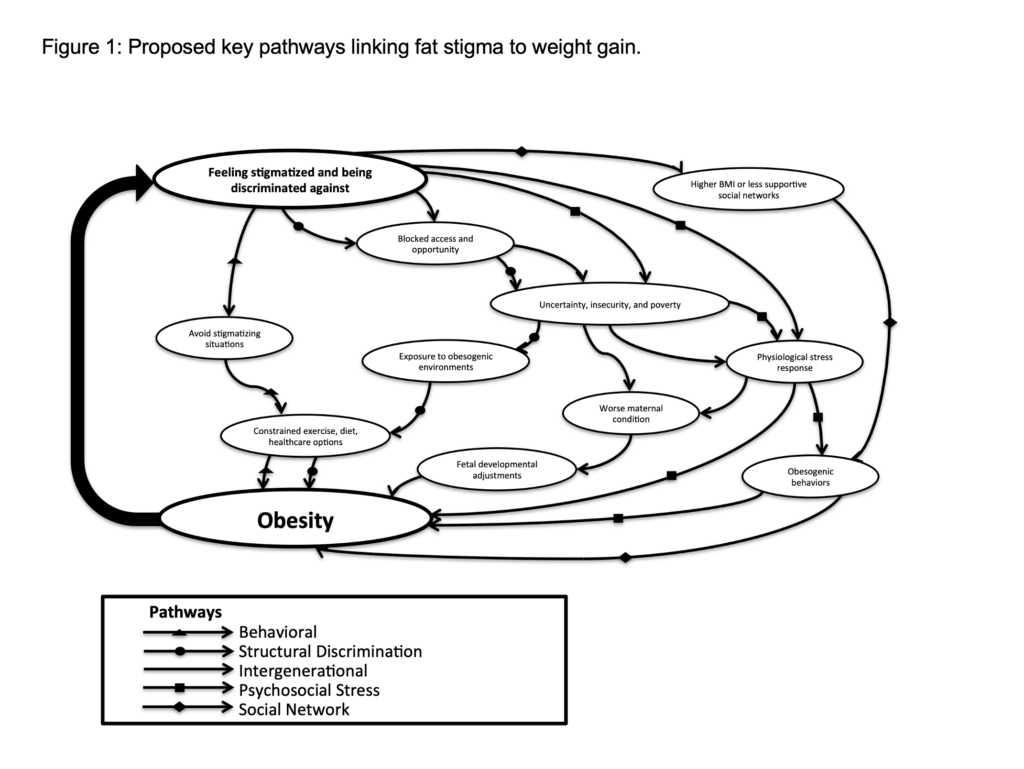

Much of my work in this space has been focused on clarifying and testing the mechanisms by which anti-obesity efforts lead to unexpected, unwanted outcomes, including depression and weight gain. Here is one model I have been working on:

Supporting Better Post-Bariatric Lives

Weight-related stigma is prevalent and often socially permitted in the US. In collaboration with Mayo Clinic – Arizona, we spent three years conducting a longitudinal ethnographic study with bariatric surgery patients. We tracked how their lives and social identities changed – or didn’t – in the wake of massive weight loss. The story proved anything but simple. Our 2021 book called “Extreme Weight Loss”, led by Sarah Trainer and out with NYU Press, was a capstone to this now-completed project.